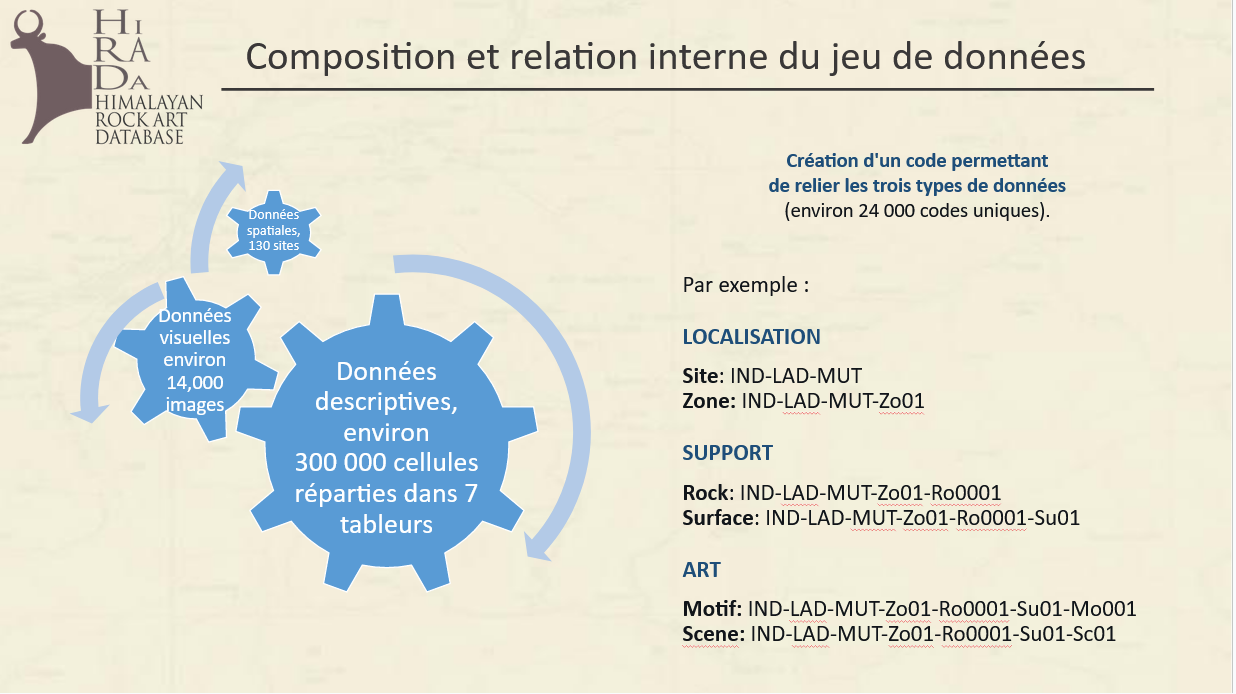

In the Western Himalayas, there have been less than a dozen excavations. Archaeological research is therefore based mainly on the analysis of surface material. Over the last fifty years, rock art has proved to be a valuable source of information, due to its quantity, diversity and immobility, for understanding the past of the Himalayas, from the Neolithic period to the beginning of the 2nd millennium AD.

After having been discovered by a few missionaries in the late 19th century and then Western explorers in the first half of the 20th century, rock art in the Himalayas has been the subject of research by a dozen or so local and international researchers since the end of the 1970s. The first book devoted to the rock art of Ladakh appeared in 2007 in the form of a catalogue, and a doctoral thesis offering an in-depth analysis was defended in 2010. Over the last ten years, recognition of its scientific importance and heritage value has increased spectacularly.

Although documentation of rock art is still sometimes carried out on an individual basis, several initiatives by teams led by personalities from a variety of backgrounds (such as NGOs specialising in heritage protection, enlightened rock art enthusiasts and academics) have recently emerged at regional, national, and international level.

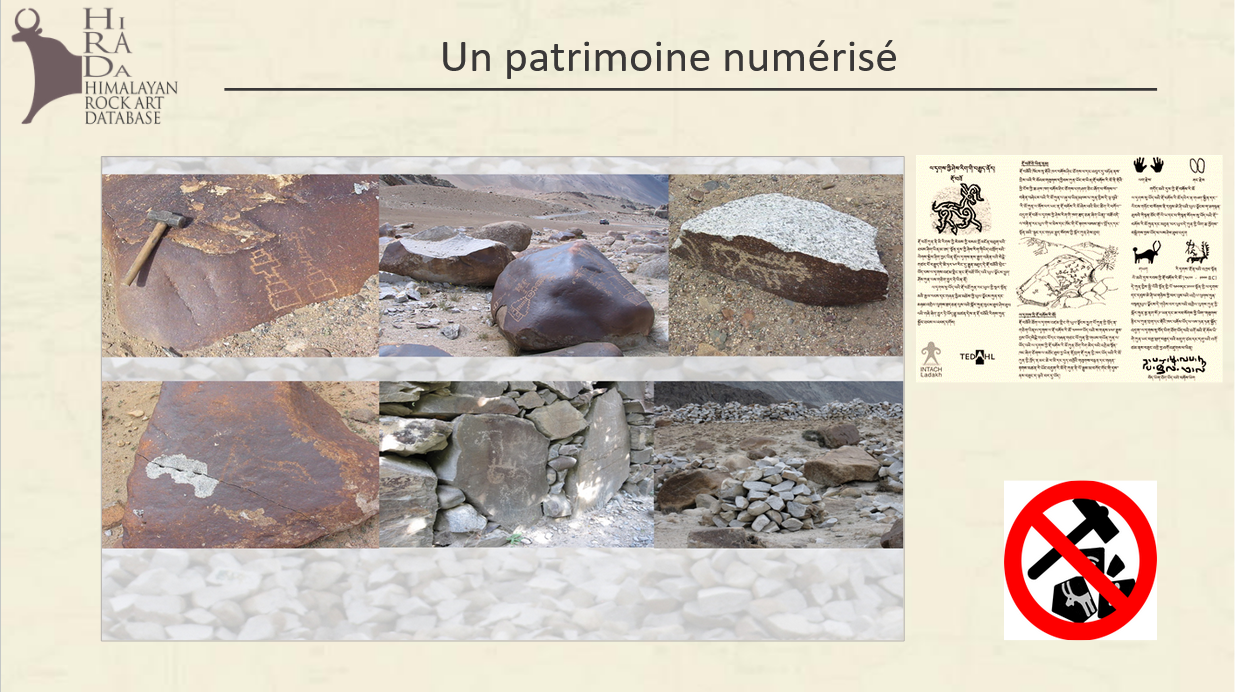

While this recent interest is to be welcomed, it is regrettable that these various initiatives often result in redundant data, at a time when many rock art sites are facing imminent threats. At best, the data collected is not comparable because each initiative follows its own system, preventing a global study. In the worst cases, the data is of little use because it cannot be processed scientifically. This is what some colleagues, who specialise in rock art in other parts of the world, call “tourist rock art”: unfortunately, in the Himalayas a large amount of published data falls into this category. These are simple lists of rock art sites, documented by photographs with no context, no survey and no notes, although the geographical coordinates of these sites are sometimes published, as in the archaeological inventory of Ladakh, which lists more than 500 rock art sites.

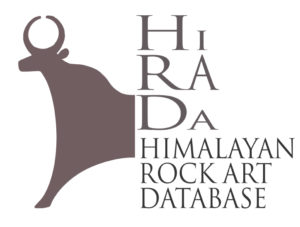

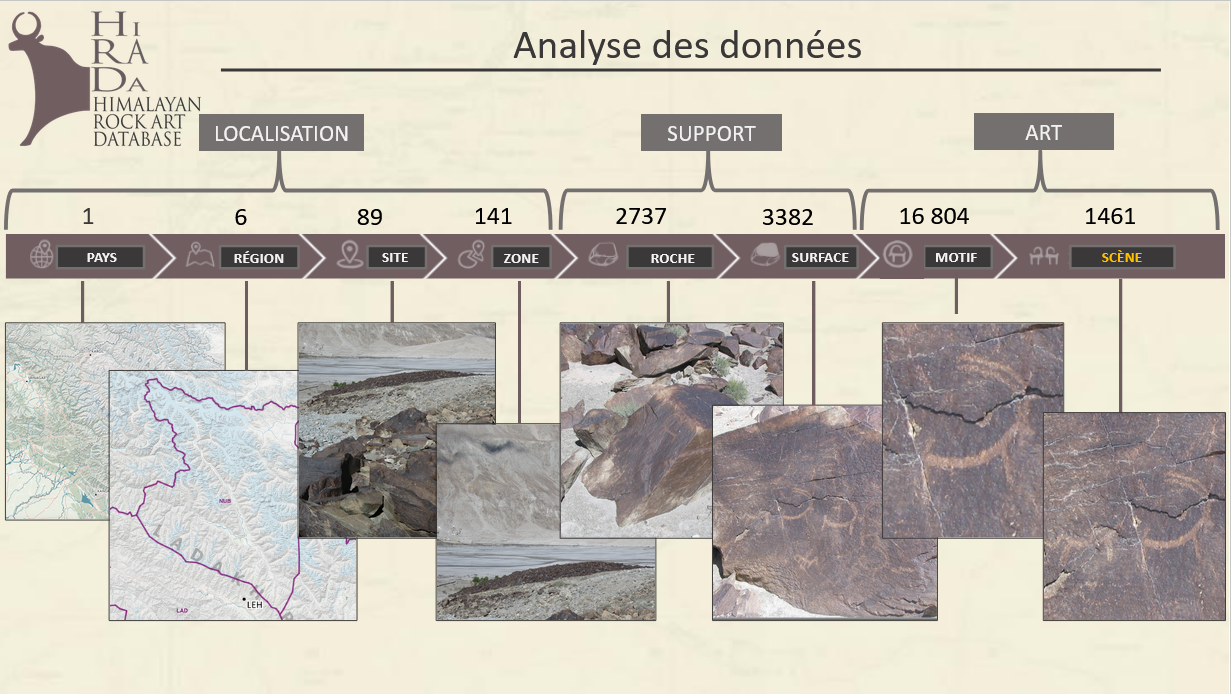

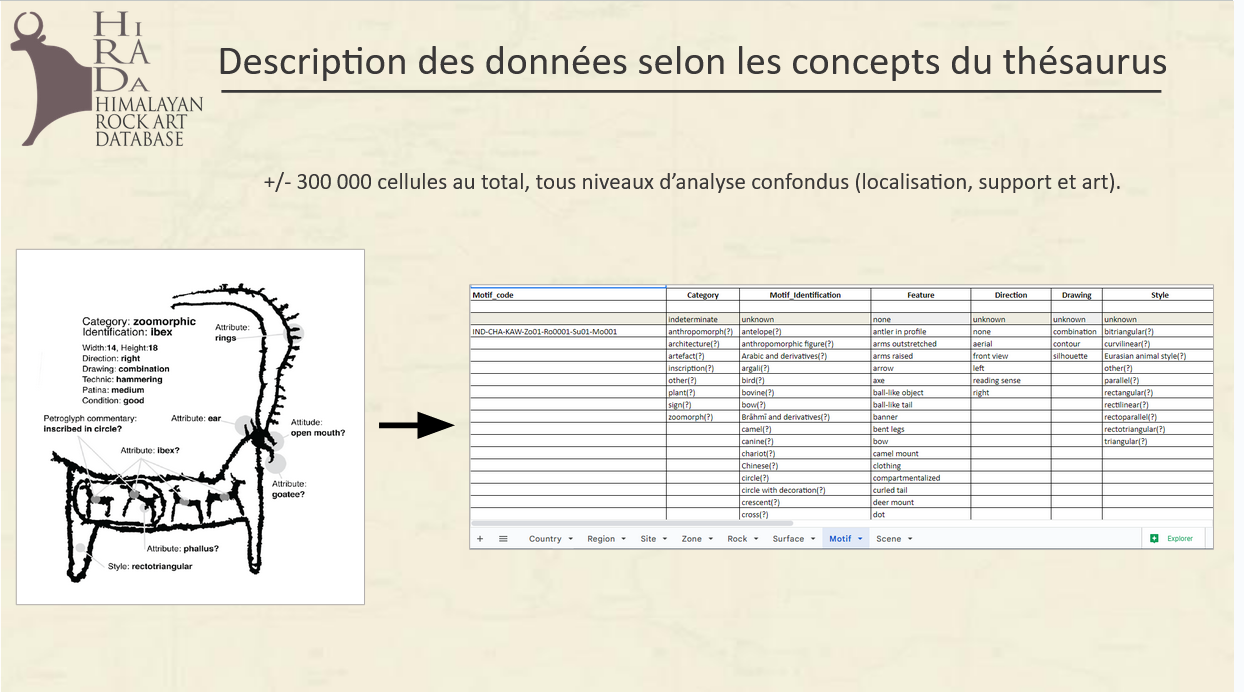

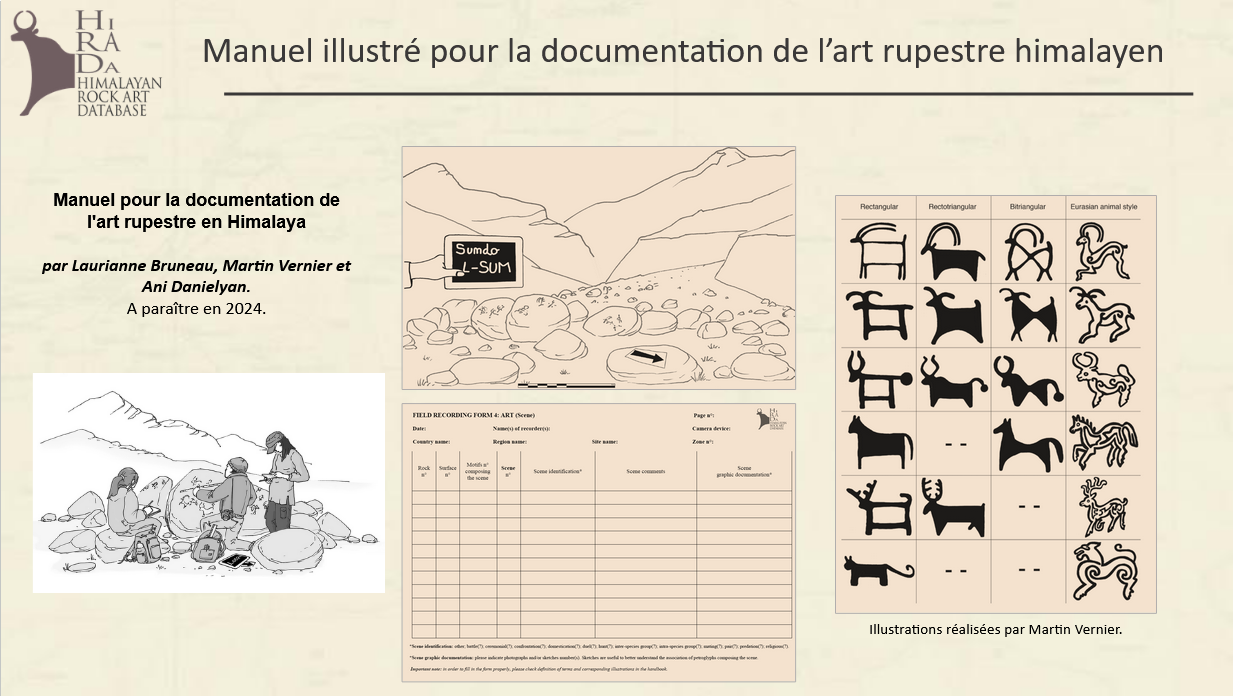

Based on this observation, we have endeavoured to construct a standardised dataset. This long and laborious stage is the necessary condition for providing a coherent framework for the interpretation of all rock art, whatever the study area, with the aim in the Himalayas of better characterising this cultural ensemble and its regional specificities.

In other words, in order to be scientifically exploitable, past and future data must be homogenised using a precise method that complies with international standards for rock art studies, while being adapted to the Himalayan context.

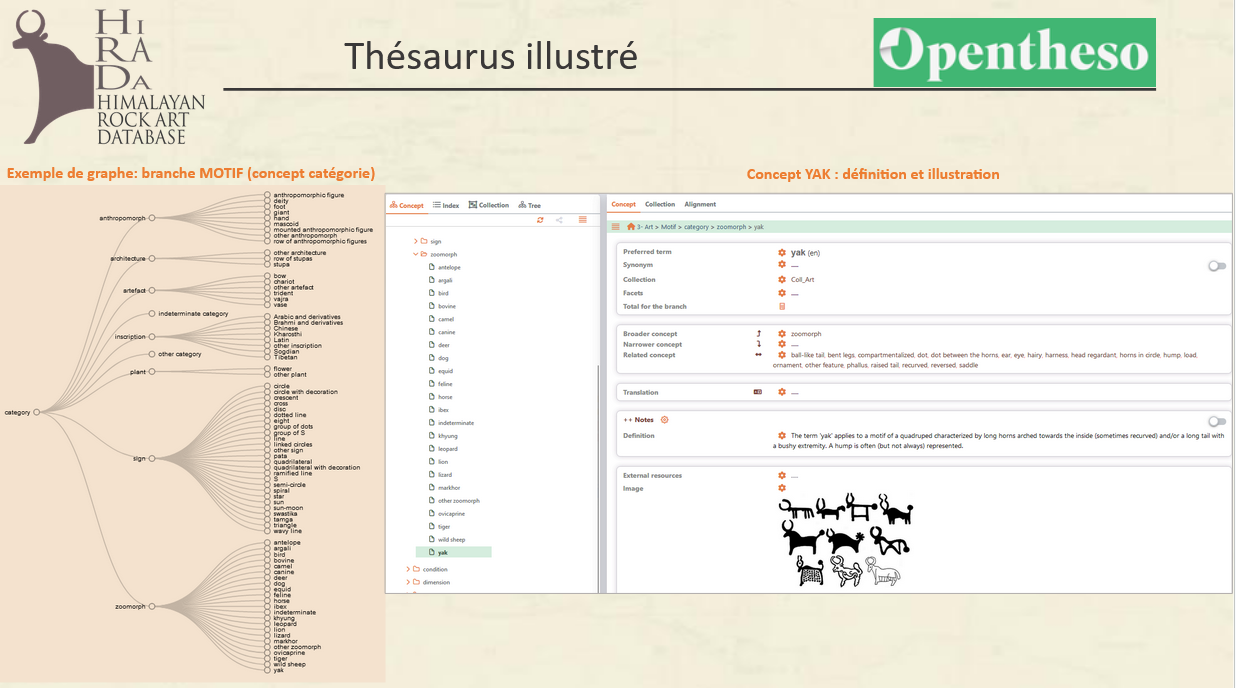

With this in mind, and thanks to the support of several institutions, commitments have been made to produce a database and a handbook that are both independent and complementary, in line with current Open Science and Digital Humanities standards. The aim of these tools is to contribute both to research and to the preservation of heritage, while guaranteeing the accessibility of the material by complying with the FAIR principles, i.e. Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable. The project is based on the services made available to French researchers in the Humanities and Social Sciences by the Research Infrastructure Huma-Num.