BUDDHIST STELAE AND BAS-RELIEFS IN THE INDIAN HIMALAYAS: 2013-2024

The long tradition of rock art in Ladakh sets it apart from other Himalayan regions. It includes Buddhist stelae and bas-reliefs, the existence of which was mentioned by the Western travellers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although stone statuary is undoubtedly one of the main sources for understanding Buddhism in Ladakh, both historically and religiously, until recently little research has been carried out into this heritage. As in the case of petroglyphs, the research that is available usually consists of simple lists of stelae and bas-reliefs, documented by photographs with little context. The geographical coordinates and dimensions of these stelae and reliefs are sometimes published.

To date, the most accomplished work on this subject is Phuntsog Dorjay’s 2006 thesis at the University of Jammu (Development of Buddhist Art in Ladakh from 800 to 1200 A.D.). . More recently, the inventory of cultural sites in Ladakh carried out by NIRLAC (Namgyal Institute for Research on Ladakhi Art and Culture, Leh) lists reliefs and stelae previously unknown to the public (Legacy of a Mountain People, Inventory of Cultural Resources of Ladakh, NIRLAC, 2008, 4 volumes). The archaeological inventory of Ladakh, published online in 2023, lists 270 Buddhist reliefs, but the context is not harmonised and above all, there is no differentiation in terms of period or workmanship.

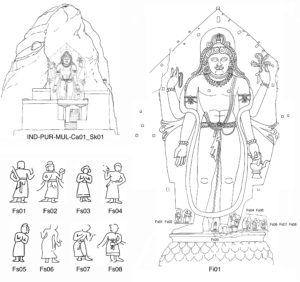

Since 2003, Martin Vernier has been compiling an inventory of the Buddhist bas-reliefs and stelae of Ladakh. After twenty years of accumulating visual documentation, this corpus was harmonised and standardised in 2023, retaining only representations of anthropomorphic figures assimilated to the Buddhist pantheon and predating the establishment of a standardised iconography according to the Tibetan canon, i.e. before the 14th century AD.

Once these selection criteria had been applied, the number of reliefs was close to 250, spread across the whole of Ladakh and the neighbouring regions of Spiti, Upper Lahaul and Upper Kinnaur. This geographical coverage follows the expansion of the MAFHI’s area of investigation for the study of rock art.

The establishment of a controlled vocabulary and the systematic production of line drawings for each engraved surface and each figure represented are also part of the project’s objectives, in order to be able to propose a standardised corpus.

All this data is now made up of spatial, visual and descriptive data organised according to the same model as the HiRADa project. Like the rock art project, it applies the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles in order to:

- make the data accessible to the scientific community as a whole, to enable multidisciplinary study;

- offer other researchers a possible and ideally collaborative repository;

- promote the protection of this heritage.

While in some parts of the Western Himalayas — such as Ladakh — there has been a revival of devotion to Buddhist steles (some have been relocated and placed in shelters, sometimes with cement bases), in other regions these remains are, at best, abandoned, but often subject to deterioration or demolition.